Panayotis Fatseas (GR) | Solo Exhibition

Curation: John Stathatos

With the support of the Museum of Byzantine Culture

Gallery

Panayotis Fatseas (GR)

Panayotis Fatseas was born on the island of Kythera in 1888. In 1910 he emigrated to the United States of America, returning two years later upon the outbreak of the Balkan Wars. He brought with him a camera, and although he had not planned on a career in photography, the demand for portraits was such that in 1920 he opened a studio in the village of Livadi. He died in 1938, at the early age of fifty, leaving behind a valuable archive of some 2.200 glass negatives. Apart from studio portraits, it included landscapes, interiors, festivities, views of the traditional procession of the Myrtidiotissa icon and other images characteristic of the pre-war island life. The badly damaged negatives were rescued and restored by the photographer John Stathatos, resulting in a major exhibition at the Benaki Museum, Athens. In her review of the exhibition, art critic Margarita Pournara remarked that Panayotis Fatseas, the self-taught Kytherian, “could be included among the five major Greek photographers of the first half of the 20th century”.

John Stathatos

The photographer, writer and critic John Stathatos was born in Athens in 1947. He studied and was based in England from 1967 to 2002, and his personal work has been widely exhibited in Europe. He has curated major international events, including the Israel Photography Biennale and the Thessaloniki Photosynkyria, and his writings on photography and art have been published in numerous books, magazines and catalogues. He contributed significantly to the emergence of Greek photographic studies through the exhibitions, and associated catalogues, The Invention of Landscape: Greek photography and Greek landscape 1860-1995, Image and Icon: The New Greek Photography -the first in-depth critical study of contemporary Greek photography- and Ways of Telling: Photography and Narrative, as well as through researching and introducing the work of Andreas Embirikos, Maria Chroussaki and Panayotis Fatseas among others. In 2002 he founded the annual Kythera Photographic Encounters and the associated Conference on the History of Greek photography. His personal publications include The Book of Lost Cities (2005) and airs, waters, places (2009). His photographs, essays and texts can be consulted on www.stathatos.net.

Information

- Duration: 26/9 – 20/10/2018

- Opening hours: Daily 08:00-20:00

- Opening: 26/09/2018,19:00

- Venue: Museum of Byzantine Culture

Co-organisation

Kythera Photographic Encounters, Thessaloniki Museum of Photography

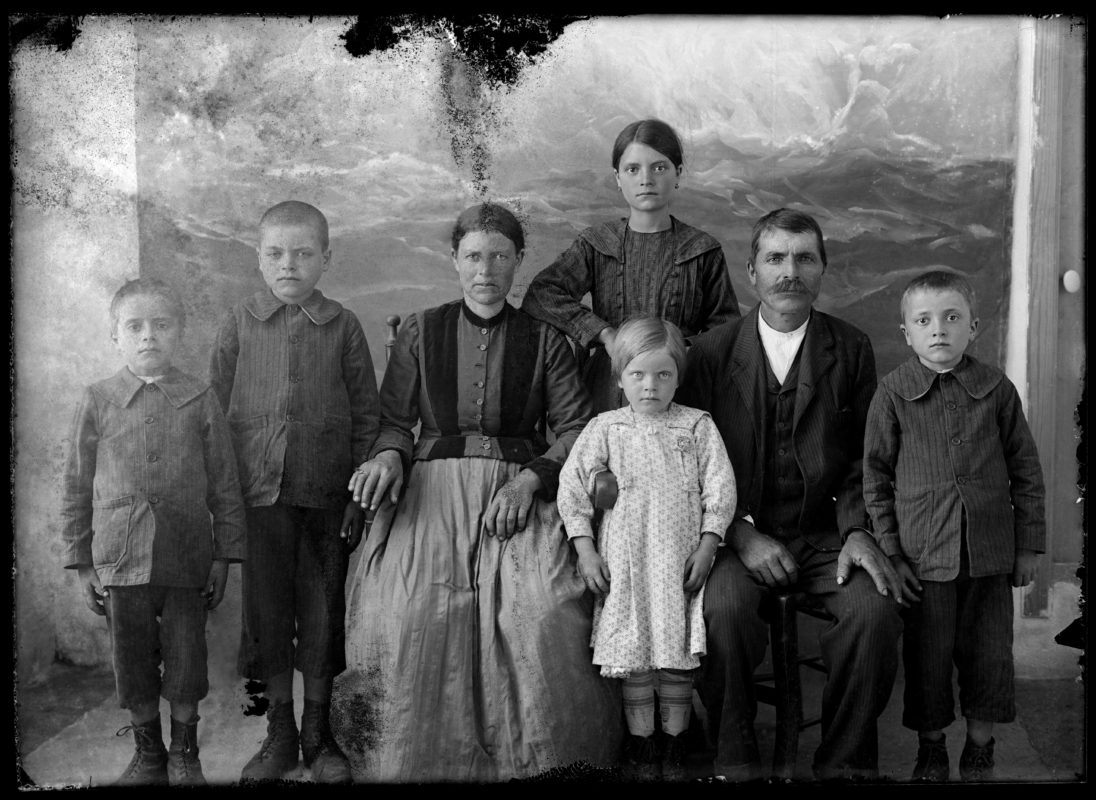

Throughout the 19th and up to the middle of the 20th century, the greater part of worldwide photographic activity revolved around small local studios. Most of their humble production, which laid no particular claim to artistry, has been lost or destroyed. However, in a few rare cases, the fluidity of the photographic medium has ensured that the work of certain almost anonymous practitioners acquires –oſten many years aſter their death– an unexpected and enduring artistic value.

Such cases in the history of photography include Eugène Atget, Mike Disfarmer, Martin Chambi, Seydou Keita and the Epirote photographer Leonidas Papazoglou. To these names, one can add that of Panayotis Fatseas (1888-1938), the first commercial photographer to practice on the island of Kythera. Fatseas’ negatives remained untouched from his death until 2002, when they were discovered by the photographer and photo historian John Stathatos, who rescued the archive and undertook its conservation. Today, Fatseas has been revealed as not merely an invaluable witness to his time, but also as a significant photographic artist of the first half of the 20th century.

The Fatseas archive consists of about 2,200 glass negative plates exposed between 1920 and 1938, most of them 12x16.5 cm in size. The great majority of the images are formal portraits but also landscapes, outdoor scenes, dances and festivities, scenes of the procession of the icon of the Myrtidiotissa and other characteristic scenes of pre-war island life. The core of the Fatseas archive, quantitatively and qualitatively, is undoubtedly made up of his portraits. The most superficial glimpse is enough to confirm how different they are from the average commercial portraits of the period. Although these images include the incidental period information, which is the usual attraction of old photographs, in this case it is unlikely to hold our attention; on the contrary, our gaze settles upon the evocative faces of the sitters, upon the postures which betray so much about them and their relationship with one another, and upon those wonderfully expressive hands. These are, it seems, paradoxically contemporary images -or perhaps, like all good art, they are simply timeless.

The Kytherians photographed by Fatseas do not seem like impersonal figures, symbolic perhaps of some nostalgically viewed past, but preserve their individual personalities. The two or three days’ wages with which they paid the photographer turn out to have been a good investment, since, alongside the postcard-sized prints mailed to a father or son in Australia, they were -all unwittingly- also purchasing a small fraction of immortality. Not just because their faces have travelled down the years to reach us, but above all because the photographer’s alchemy proves such that before these miraculously resurrected photographs we pause involuntarily to study their image and wonder who they were, how they lived and what passed before their eyes. Immortalised by Fatseas, they are simultaneously other and familiar.

John Stathatos